The most consumed in Bhalil - © 2023

Handmade from silk - © 2023

As always, a safe bet - © 2023

Green olives: delicious in tagine dishes - © 2023

The most consumed in Bhalil - © 2023

Handmade from silk - © 2023

As always, a safe bet - © 2023

Green olives: delicious in tagine dishes - © 2023

BHALIL. Some symbols of local economic and commercial activity. Copyright © 2023

A few decades ago, the people of Bhalil lived mainly from agriculture. The men worked in the fields, while the women took care of the home. A few people ran small businesses, mainly selling basic foodstuffs (sugar, salt, spices, washing powder, soap, etc.). If I remember correctly, it was in the 1960s that young women began making silk ‘buttons’ for traditional clothing (kaftans, djellabas, etc.) to earn a little money. Very few people were civil servants. At the same time, or even a little earlier, young men in good physical health went to work in Europe in sectors where labour was needed . The glorious 30 years. There was a lot of hiring in construction and agricultural harvesting (tomatoes, grapes, corn, etc.). Other Bahloulis became soldiers. Retirees appeared in Bhalil much later (returning to the village to live out their days). Over time, things changed little. However, there were more shops and more houses were built (people had to leave the caves, caverns and cellars one day). But also more stray cats and dogs. Fewer cattle and chickens with their young outside. Also, less mud in the streets (it was painful to walk in the mud). I admit that paving stones are better. But they need to be of better quality. The paving that was in the historic centre (Khandaq) until recently was made of limestone, which is sturdy and durable but slippery when it rains. I'll have to go and see what the new paving looks like. In the meantime, it's a shame about the plane trees that have been removed. Something could have been put in their place. Perhaps trees more suited to the terrain. Vegetation is more welcoming for visitors and for... biodiversity. And so we don't have to hear on YouTube (rightly or wrongly) that the village resembles a Moroccan version of a Brazilian favela: The Moroccan favela and the cave dwellings of Bhalil, Morocco.

When it's olive season, it's also a bit of a celebration. With a price of €0.5 to €0.6 (5 to 6 DH) per kilo of olives in December 2021, and around €5 (50 DH) per litre of olive oil at the same time, there are some bargains to be had. The yield can reach 25 litres of oil per 100 kg of olives or even more, depending on the fields, maintenance, etc. However, harvesting can be difficult and the yield low. It can drop to 10 litres of oil per 100 kg of olives or even 5 litres. Olive cultivation in Bhalil does not generally require irrigation. A good or bad harvest will therefore depend on the rainy season. In the evening in the village, after a hard day's work, you can smell the aroma of cooked minced meat. We peel mandarins and drink mint tea, etc. Some of us go to the café to eat or play cards. In short, we relax as best we can, waiting for the next day. This lasts about a month. It's an alternation between working in the fields and well-deserved rest in the village. You will find a story about the olive harvest in the memory chapter. Here is the link: Bhalilone 5 and the Attack of the Olives. Any reference to Babylon 5 or Attack of the Clones in Star Wars is purely coincidental.

Cultivation areas: the Aggay wadi, Mimet, Jnane El Aïn, Quadoussa, etc. More vegetables are grown and much less fruit, if any at all. Fruit was more of a luxury for the people of Bhalil. Bananas and yoghurt were given to the sick. Sometimes apples. In Aggay, the favourite vegetables are tomatoes first and foremost. Next come cabbages, peppers, green beans, etc. Peas were more rare. In other fields, potatoes dominated, or even broad beans. The latter were, and probably still are, eaten in all kinds of dishes. From small green pods, cooked like green beans, to dried broad beans, crushed and cooked like mashed potatoes (Bissara) or like crushed peas. Not to mention whole dried broad beans cooked like other legumes. This last broad bean dish is like concrete in your stomach! It's solid and keeps you going well in winter. In areas where there was enough water for irrigation, corn was sometimes grown. But this was not common. Among the most famous fruits in Bhalil are the famous figs. Unfortunately, when fig trees are neither protected nor monitored, everyone helps themselves . In this area, respect for private property is not a major concern. As for prickly pears, it's the same story, only more difficult with the cactus thorns ! In any case, growing fruit trees in Bhalil requires investment and protection if you want to harvest the fruit. Otherwise, bye bye dessert!

Unusual question: is there a link between potatoes and caves in Bhalil? Are potatoes

‘troglophilic’? When did people start eating potatoes in Bhalil?

To answer all these highly strategic questions, let's start by briefly recounting the origins of the potato.

We know that the potato comes from the west coast of Latin America. Its history began

with that of the Native Americans over 10,000 years ago, and it was domesticated around 8,000

years ago. It eventually arrived in Spain in 1534 after the discovery of America in 1492. They

spread to the rest of Europe from 1588 onwards. Their introduction to Morocco logically

postdates these dates. To be sure, we examined the digital archives of the

BNF Digital Library: Gallica provides us with some

answers. Indeed, there are two documents in the form of complementary articles that discuss

potato cultivation in Morocco.

As luck would have it, and curiously enough, these same documents mention a village

located in the Middle Atlas Mountains called... Bhalil (alias Bahlil)!

A first article in the journal " Applied Botany

and Tropical Agriculture was written by

Emile Miège

(1880–1969) on 1 September 1935 on 6 pages (676–681). And a second, shorter article

appeared in the newspaper " Le Matin " dated 5 November 1935 on the same subject. The second

article echoes the first. For a better presentation on this website, these two articles

have been edited beforehand.

To unravel the mystery of the connection between potatoes and the caves of Bhalil, as well as the ‘age’

of the potato in Bhalil, I invite you to read these two articles in PDF format:

Article 1 (Review) and

Article 2 (Diary). Bon appétit!

If the field allows it, cereals are grown. Preferably on flat land without olive trees. In terms of varieties, there is not much choice: barley and wheat. Sometimes oats for the animals. Fresh, warm barley bread is really delicious with olive oil and a glass of mint tea. But barley or wholemeal bread are still frowned upon in Bhalil. It has to be white. So sometimes they grow ‘Farina’ wheat, which produces a whiter flour and bread. Inevitably, one day, as in Europe, we will move towards consuming wholemeal bread. It is darker and tastes better, but it is also more expensive. So we must enjoy it before the trend reverses! Women, usually housewives, prepare the bread dough themselves and bake it in public ovens. It can also be baked in a kitchen oven, for those who have one. Private ovens appeared in Bhalil later, in the 1980s, I would say. They were made locally by the welder. Of course, you had to be able to afford to buy one. It was a luxury not to have to take your dough to the public oven and then go back to collect your bread. Not very pleasant when the weather is bad. The public ovens in Bhalil mainly use wood, but also sawdust, olive mill waste, etc. Anything that burns is used! The same technique is also used to heat the water in public baths.

Baaaaa.... Moooo...

Of course we can hear the sheep and cows! And of course there are

fewer of them in the village. Part of the population of Bhalil lived and certainly still lives

off sheep and cattle farming. What I remember most is that in Bhalil

many people had their own cow, which they entrusted to a shepherd every morning to

take out to the fields with the other cows. The cows spent the day among

friends grazing in the fields and hills. In the evening, they were released at the entrance to the

village. They found their own way back home. As a child, when I

was playing with my friends, I would sometimes come across our cow. I would say, ‘Ah! It's our cow.’

So I would accompany her home to make sure she got back safely. Individual cows

provided milk for families. From time to time, they gave birth to

a calf. With sheep, it was different. We didn't have individual sheep.

Farmers had specialised land for keeping their flocks. Each piece of land

was called a ‘Zriba’.

These

fields were very close to the old Bhalil. You had to keep an eye on your sheep.

The flock would go out to the fields with a shepherd, just like the cows. Families

only had their own individual sheep for a few days (sometimes just the day before) before the

sheep festival (Eid al-Adha). In fact, we celebrated the sheep. That's how it was. In the past,

it was practically the only occasion for some families to eat meat.

As for goats in Bhalil, they were quite rare. Very few people owned them...

As for livestock farming and agriculture in the village, they did not mix well.

We regularly heard about conflicts breaking out between farmers and livestock breeders,

following the partial or total destruction of a crop by a herd of livestock. In the

same way, we heard about this or that livestock breeder who had his herd stolen during the

night. In addition, and mainly for their own consumption, people sometimes kept a

small domestic herd of chickens, rabbits, pigeons, etc. Hunting outdoors

was rare and fishing non-existent in the absence of any bodies of water. We had to wait

weeks or even months before we could eat fish. I mean sardines.

They are made by hand using traditional methods for traditional clothing (kaftans, djellabas, etc.). The raw materials are limited to two items: silk thread and paper. The main tool used is simple: a small square rod approximately 15 cm long, pointed at one end and wider at the other. It is accompanied by a medium-sized sewing needle. Obviously, this craft requires a certain amount of time to learn. Later on, one acquires speed in execution, capacity for innovation, etc. Talent is of course always welcome ! I didn't know that Sefrou, along with its surrounding region (Bhalil, etc.), was considered by the Ministry of Tourism and Handicrafts to be the world capital of silk button manufacturing! (PDF: Silk buttons). In Bhalil, it is a source of income for many families and is exclusively women's work. Provided they have a little time outside their usual tasks (taking care of the home, studying, etc.). Some women are of course more talented than others, and it could take beginners two to three years to learn the craft. They did not start learning how to make silk buttons straight away. First, they had to do some unpleasant household chores. As they say, "start by bringing the coffee and we'll see after that". Then, chores and learning were combined little by little. The secrets of the craft were not handed over freely to the first person who came along, all at once. Usually, the women or girls would meet in the afternoon when there was less work to do at home, on a street corner, to start production. It was obviously better when the weather was nice. Sometimes there were dedicated premises where women could meet to make buttons. It was like going to work! These premises were run and managed by other women who acted as ‘managers’. They imposed strict rules, with the sole aim of increasing production. For example: ‘If you talk, you make a silk button for others,’ etc. But we went there because we were less disturbed than at home. On the other hand, I don't think it was free. The female ‘managers’ were probably paid in silk buttons for services rendered. There are several models of silk buttons that can be made in Bhalil. Some models are more difficult to produce but sell for more money. Others are easier to produce but bring in less income. Not all women are capable of producing all models. The most talented women quickly acquire a reputation, and their work is in greater demand. As with any craftsman who is more skilled in their trade. These women are able to reproduce ‘bespoke’ buttons to order from a model or sample they have never seen before. I understand that in Bhalil, the models called ‘Mdabra’, ‘Ssam’, etc. are no longer made. In short, more skilled labour and more elaborate models bring in more money. Sales to village intermediaries are made on a per-unit basis. It is probably difficult to become wealthy by producing silk buttons with your own hands. However, it is possible to do so by acting as an intermediary between producers and customers in large cities. This requires a network for collecting buttons within the village. Another network is needed for distributing the buttons in the big cities. And yet another for purchasing the raw material (silk thread) in the big cities as well. The women of Bhalil are small local producers who supply the rest of the chain. However, they are not the ones who earn the most from this business. Better organisation of these women, in an association or cooperative, could perhaps help them to get the most out of their production. This is similar to what is done in Sefrou: Cherry buds.

As we said, we went from caves, cellars and cave dwellings

to solid outdoor constructions. At first, the walls were just a

pile of stones placed side by side to mark the boundaries of the property (a cellar, for example). Then

there were walls made of stones and a weak binder (earth and lime?). And finally,

walls made of stones or concrete bricks, with a stronger cement-based binder. Luxury.

The problem with uninsulated exterior walls is that they are very cold in

winter and very hot in summer. This results in temperatures that are too cold or too hot in the house.

Overall, we continue to build this way. Is it a lack of resources or a lack of knowledge?

The simplest and most obvious solution is to have double external walls with air in between.

Air is a good insulator, but stone and concrete are not. Okay, a double wall costs

more than a single wall. But other means of insulation are more expensive and more difficult to

install. Not to mention double glazing! That's science fiction!

For the floor, it's really easier. Without pretending to be an insulation expert, here's what

a construction company installed for us to replace the concrete screed in our basement,

which was completely cracked (this also applies to a ground floor without a basement). From bottom

to top:

➀ Layer of gravel + sand + crushed stone (Drainage: 1st damp-proof course) ≈ 3 cm.

➁ Polyethylene film (polyethylene sheeting). Minimum thickness of 150 µm (waterproofing).

➂ Polystyrene layer (Thermal insulation) ≈ 3 cm.

➃ Reinforced concrete slab (to prevent cracks) ≈ 6 cm.

➄ Levelling (≈ 3 cm).

➅ Covering: tiles, mosaic, etc.

Of course, the thicker the better! It's a question of resources and height.

Useful links for insulating parts in contact with the ground:

Concrete & Polyane -

Foundation footings & walls.

The building sector in Bhalil, as everywhere else, is developing rapidly. This is normal, as there are

more and more people in an increasingly smaller area available for construction. If I have understood correctly,

an apartment in Bhalil costs between 250,000 and 300,000 dirhams (25,000 to 30,000 euros in 2022).

This is not within everyone's reach. And that's why people prefer to

build themselves, especially if they own a piece of land. In any case, the building

always provides work for contractors, architects, masons, building craftsmen,

labourers, building material stores, hardware stores, etc.

The usual! Nothing special in that regard in Bhalil. And as everywhere else in the world,

if you have money and don't know where to invest it, property is a lower-risk option!

We are in Aghezdis, more precisely between El Kaddous courtyard and the Jmaâ crossroads.

In this upper neighbourhood, there were a few shops selling basic goods and a few

specialist shops: hairdressers, tailors, ‘recyclers’ (i.e. middlemen)

selling silk buttons, tobacco, etc.

‘Go to Khali Hammou's and bring back some matches.’ This was the kind of sentence children regularly heard

when sent on an errand. Khali Hammou's was the shop on the corner of the street where

we lived. It was 25-30 metres from the house. We went there to buy things that weren't

produced in the village:

matches, sugar, washing powder, soap, spices, lemonade, sweets...

Other products such as butter, milk, oil and bread didn't need to be

brought in from outside the village (they were produced locally). Some people produced their own

local products. Not everyone produced everything. But we also went to Khali

Hammou's to slaughter a chicken, a rabbit, pigeons, or even a hedgehog. It was complicated

to slaughter a hedgehog. But Khali Hammou knew how to do it. He had the technique. The nearest butcher's

shop was in the historic centre of Bhalil. You had to go down and up the

cliff to buy meat (beef or lamb).

Since then, small everyday shops have evolved somewhat in Bhalil. Nowadays, you can buy

yoghurt and a SIM card at the same time in one shop.

There are more shops selling more things, and there is less need to

go to neighbouring towns to buy certain products. This is normal, as Bhalil has

grown and the market has expanded. However, the choice

remains very limited compared to what you can find in a big city. So you'll

find it harder to buy a USB stick, or even a pair of trousers, in Bhalil.

In the past, there have been a few attempts to set up manufacturing businesses

(pastry, leather, etc.). But not for long.

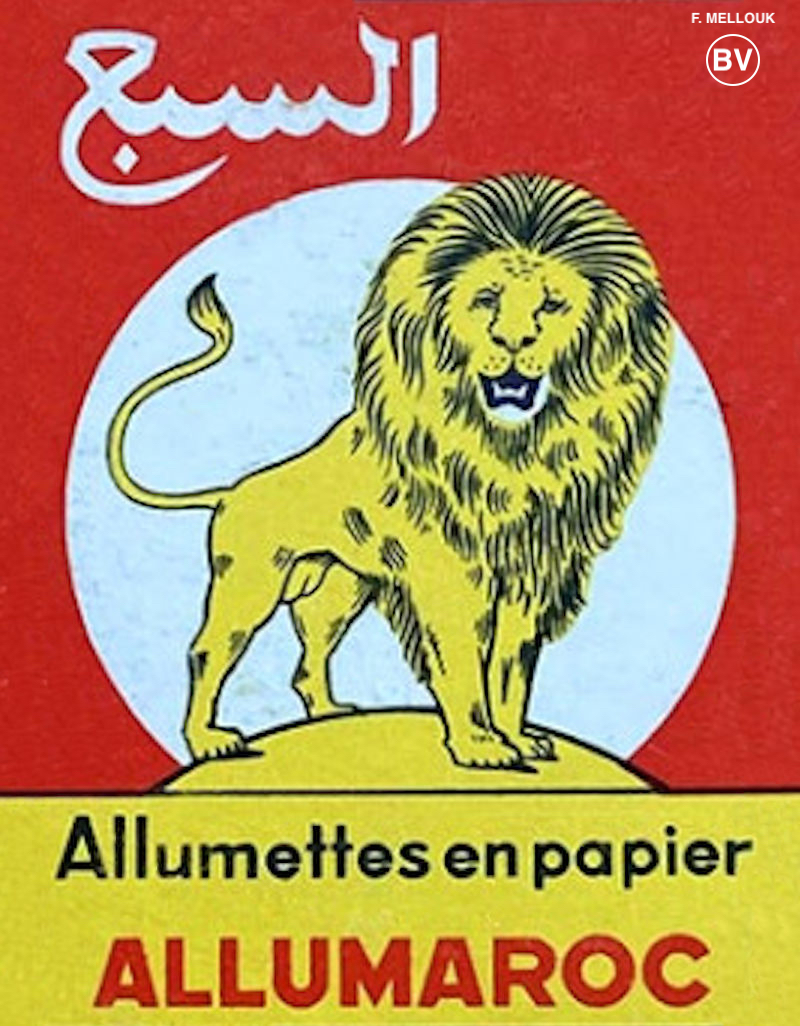

Paper rods, but effective.

Widely used for mint tea.

A little above ‘Favorites’ cigarettes.

Matches perfectly with ‘La Faucille’ soap.

BHALIL CITY 🔹 LE 360.MA 🔹 LIBÉRATION 🔹 RESOURCES ☀ TOP OF PAGE

PRODUCTION & DESIGN: Fouad MELLOUK ☀ DATE OF PUBLICATION: April 22, 2023 ☀ UPDATE: May 20, 2024 ☀ CATEGORY: Discovery - History - Memory - Memories ☀ DOCUMENTS, IMAGES & TEXT: All rights reserved. No reproduction without express permission ☀ CONTACT: bhalilvillage@gmail.com ☀ COPYRIGHT © 2023